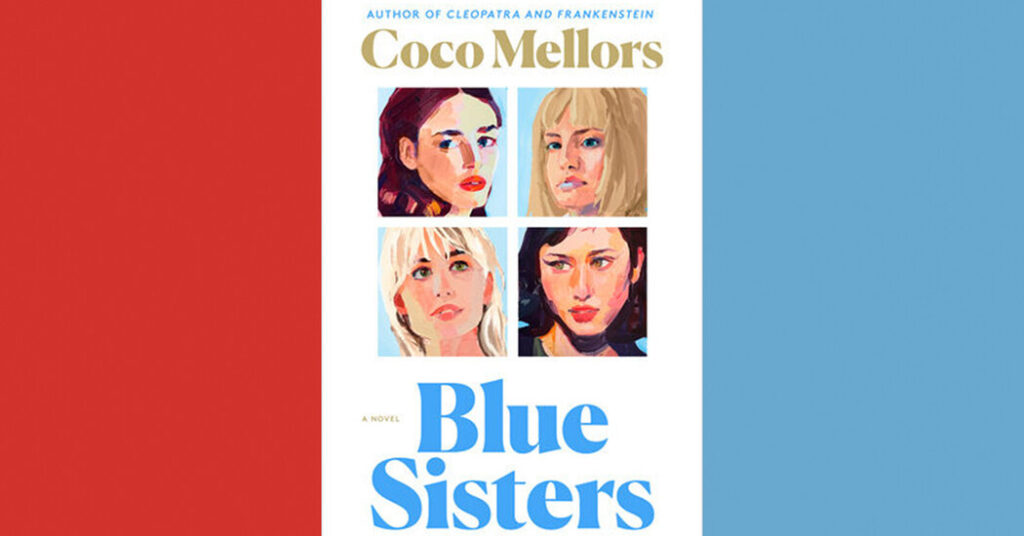

“A sister is not a friend.” So begins Coco Mellors’ sophomore novel, “Blue Sisters,” whose three adult protagonists are in constant battle — with each other, with their various addictions, with their own bad selves. For Mellors, these battles are what define sisterhood, a “tough, clumsy, unpleasant, yet essential” umbilical cord: “You’re part of each other from the beginning.”

In warm, cozy prose, Mellors guides us through the lives of Avery, Bonnie, and Lucky Blue, reuniting to clean out their childhood apartment in New York City on the first anniversary of their sister Nikki’s death. Between the ages of 26 and 33, the trio lead extreme lives that sometimes seem at odds with a domestic novel that otherwise celebrates physical beauty. Avery, the eldest, lives with his wife in London, where she quit heroin to become a successful corporate lawyer. Another sister, Bonnie, is a bouncer turned champion boxer in Los Angeles whose “drugs of choice are sweat and violence.” The youngest, Lucky, has been a model since she was 15 and lives in Paris. “She has said the words I want a drink 132 times this year so far.”

Nikki’s life was comparatively quiet: the sensitive sister “a carnival of emotions she never tried to hide,” living on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where she taught high school English “10 blocks from where she grew up” and yearning to be a mother. As the sisters reckon with her loss—to the overdose of painkillers she secretly took, to the chronic pain caused by her endometriosis—they must also come to terms with their own relationship with addiction, which “runs through them all like lightning. Through a circuit.” .”

Avery’s “boring”, perfectly composed, quiet life begins to crumble under the weight of her grief when she cheats on her wife, Chitty – a 40-year-old physician who forces her to have a child – with Charlie, a poet. meets her with In Alcoholics Anonymous. Lucky’s 20-something, fashion-party badass — doing drugs in the bathroom, hooking up with strangers, living “in the moment and seconds ahead” — only leaves her feeling more alone, wanting to “feel nothing.” to be Nothing.”

Bonnie, who has never had a drink in her life, describes herself as addicted to “pain”; And after finding Nicky’s dead body — “it looked like something that had just been spilled, like a vase of violets tipped over” — she takes out her anger on the racist patron of the bar where she works, beating him to a pulp. Even in New York, the same physical energy emerges as Bonnie tackles Lucky to the ground in an attempt to stay sober (“She was so rough, like when they were kids”), and then again in an explosive fight with both of her sisters who Starting with T-shirts Nicki saved from the Spice Girls reunion tour they all attended as kids.

For all of Avery’s AA rhetoric about reaching out to a “higher power,” it’s Bonnie who actually confesses to believing in one, a God-like figure who is “someone for me to talk to,” she self-consciously tells him at the end. From the book, the trio is made from a T-shirt fight. “I think they’ll take care of Nicky until we see her again.”

Even Avery and Lucky believe it or not, the conversation has its own power, as the trio falls into “fits of giggles” during Nicky’s funeral, an “inappropriate and inappropriate” but necessary comfort — “even Nicky would have laughed.”

Although not all of Mellor’s metaphors are grounded (addicts are compared to rats; both “had no collarbones”) and her prose can break into sentimentality, she is able to capture the strangeness, stickiness, and beauty of both sisterhood and grief. As Avery says to Lucky about AA: “Yes, the formulas were cheesy, but they worked surprisingly well.” Words have their role, and sisters have theirs.

Post Take a hard look at family history of overdose addiction appeared first New York Times.